The Pyrenean ibex was one of the four subspecies of the Spanish ibex. It was the first animal to be brought back from extinction through cloning of the last individual and also the only animal to go extinct twice. It had three other subspecies, two still surviving and one extinct. Scientists don’t know how this animal went extinct but some hypotheses include hunting, overgrazing, and disease.

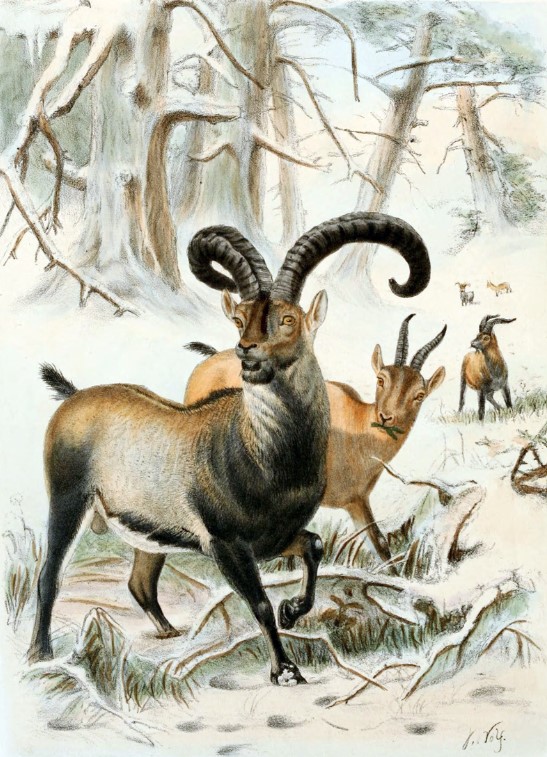

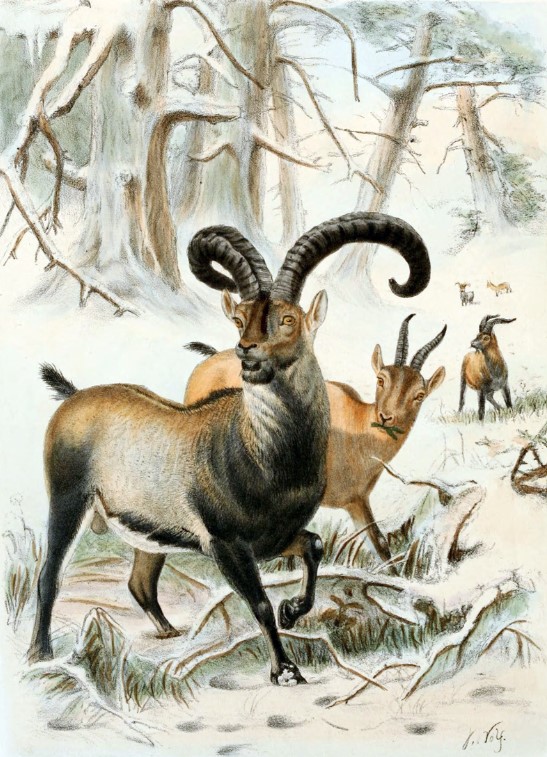

The Pyrenean ibex had short hair which varied according to seasons. During the summer, its hair was short; in winter, it grew longer and thicker. The hair on the ibex's neck remained long through all seasons. Males and females could be easily distinguished depending on the difference in their color, horn, and fur. Males were grayish brown decked with black in several places like the forehead, mane, and forelegs. The male transformed from a grayish brown to a dull grey and where the spots were once black, they became dull and faded. Females were brown throughout the summer and didn’t have black coloring like the males. Young ibex were colored like females until their first year. The male had large, thick horns, curving outwards and backward, and into a swirl. The female had short, cylindrical horns.

The Pyrenean ibex is one of the four subspecies of the Spanish ibex. The other three include the Western Iberian or Gredos ibex, the Southeastern Spanish or Beceite ibex, and the Portuguese ibex, which is now extinct. Pyrenean ibex migrated according to seasons. In spring, the ibex would migrate to more elevated parts of mountains where females and males would mate. Females would separate from the males so they could have their babies in isolation. They gave birth to one kid in May and migrated to less snowy places in winter. They mostly feed on vegetation such as grasses and herbs.

The Portuguese ibex went extinct first, in 1892 with the Pyrenean ibex coming second, in 2000. Scientists don’t know what caused the extinction of this animal. Some hypotheses are continuous hunting, overgrazing, and diseases from domesticated animals. Pyrenean ibex were found in large numbers in the Pyrenees region, but the count gradually went down in the 19th and 20th centuries because of continuous hunting. In the latter half of the 20th century, a small number of individuals survived in Ordesa National Park in the Spanish Central Pyrenees. The last one, named Celia, died in 2000 when a tree fell on her.

The last specimen, Celia, was taken by Spanish biologists. They took skin, tissue, and blood samples for possible cloning, which were cryopreserved. The first cloning attempt in July 2003, ended in vain. The success came in January 2009 when the Pyrenean ibex became the very first extinct animal to be resurrected. Scientists successfully implanted 57 embryos into surrogate female domestic goats. Just seven embryos resulted in pregnancies, and only one gave birth to a female Pyrenean Ibex. She died several minutes after birth due to a lung defect. Despite this setback, cloned cells of Celia taken by a research team are still being studied in an attempt to create hybrids. Cells for this organism are alive and frozen, giving this an advantage over bringing back extinct species like mammoths who have very ancient DNA. Still, reproductive biotechnology has a long way to go before communities can be replicated or brought back.